- constituting a separate entity : individually distinct <several discrete sections>

- a : consisting of distinct or unconnected elements :noncontinuous

b : taking on or having a finite or countably infinite number of values <discrete probabilities> <a discrete random variable>

In order to make the claim that a situation is "individually distinct" and consists of "unconnected elements", we would have to identify the boundaries that define it's beginning and end. Bitzer argues that "rhetorical discourse is called into existence by ... the situation which the rhetor perceives amounts to an invitation to create and present discourse" (9). Since there are an innumerable number of factors--many of them unconscious--that bring about each situation and it's perceived necessitation for the creation and presentation of discourse, how can we say when a situation has officially begun? Furthermore, given that one situation can set in motion a chain of diverse reactions, behaviors, and "counter-rhetoric" (which, in turn, may invite further response) can there truly be a definitive point at which we can safely say the situation has come to an end? By the same token, if some elements involved in perceiving the existence of an exigence and in conceptualizing what constitutes a "fitting response" are unconscious--and most would agree they are--it seems unlikely that we could count or assign variables to these elements. In other words, to draw a boarder around a rhetorical situation would be to claim to knowledge of things seemingly impossible to know.

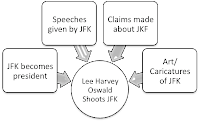

In the unlikely event that we were able to identify each element of a rhetorical situation, the utility of doing so is unclear. In thinking of rhetorical situations, I am reminded of the butterfly effect. The butterfly effect comes from chaos theory, and states that "small changes in initial conditions can lead to large-scale and unpredictable variation in the future state of the [non-linear] system" (Merriam-Webster, 2011b). To be considered non-linear, a system can not be directly proportional (i.e., one variable is constantly a multiple of the other), nor can it satisfy the superposition principle (i.e., the total effect of two stimuli at one point is equal to the summed effect each individual stimulus). This seems true of rhetoric. It seems unlikely that one piece of rhetoric could be a constant multiple of another. Is a speech always twice as effective as a one newscast, and four speeches equal to two news casts? Probably not. Nor is it likely that we could determine whether the effect of a newscast and a speech on the assassination of JFK is equal to twice the effect one would have had without the other. The butterfly effect theory draws it's emblematic name from the classic example of the butterfly: the flap of a butterfly's wings in one part of the world could, theoretically, lead to a hurricane in another. To surmise this sort of cause-uncertain effect model to rhetorical situations seems, to me, more plausible than to claim the situations are discrete. As Edbauer points out, "Bitzerian models cannot account for the amalgamations and transformations--the viral spread--of ... rhetoric within its wider ecology" (19).

References

Merriam-Webster. (2011a). Discrete. In Mirriam-Webster Online. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/discreteMerriam-Webster. (2011b). Butterfly effect. In Mirriam-Webster Online. Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/butterfly%2Beffect

Photo Credit

|

Agreed wholeheartedly. I think that Bitzer was on to something when he said that rhetoric required a certain rhetorical situation, but that situation could arise from anything and connect to other rhetorical situations anywhere as we saw with the "weird" rhetoric - despite there being three different exigencies, the rhetoric linked all three together and strengthened their affect altogether as a result.

ReplyDeleteYou’re right. Rhetorical situations brought about and/or acted upon by human beings are anything but discrete. First of all, it is difficult to state the beginning and end of each rhetorical situation as there are many topics that have been debated for years. For example, would anyone be able to say exactly when anyone began debating whether or not there was a god? In order to even attempt to tackle this question, someone would have to go pretty far back in history. Also, when a rhetorical situation does come to a conclusion or an “end,” those who study rhetoric will be studying and analyzing each component of that rhetorical situation till the end of time. Secondly, rhetorical situations do not consist of unconnected elements. Those who study rhetoric know this and understand that often ethos, logos, and pathos can intertwine and can sometimes be hard to separate into its distinct categories.

ReplyDelete